New Tool Images Uterine Contractions in Real Time to Identify High-Risk Pregnancies

Posted on 16 Mar 2023

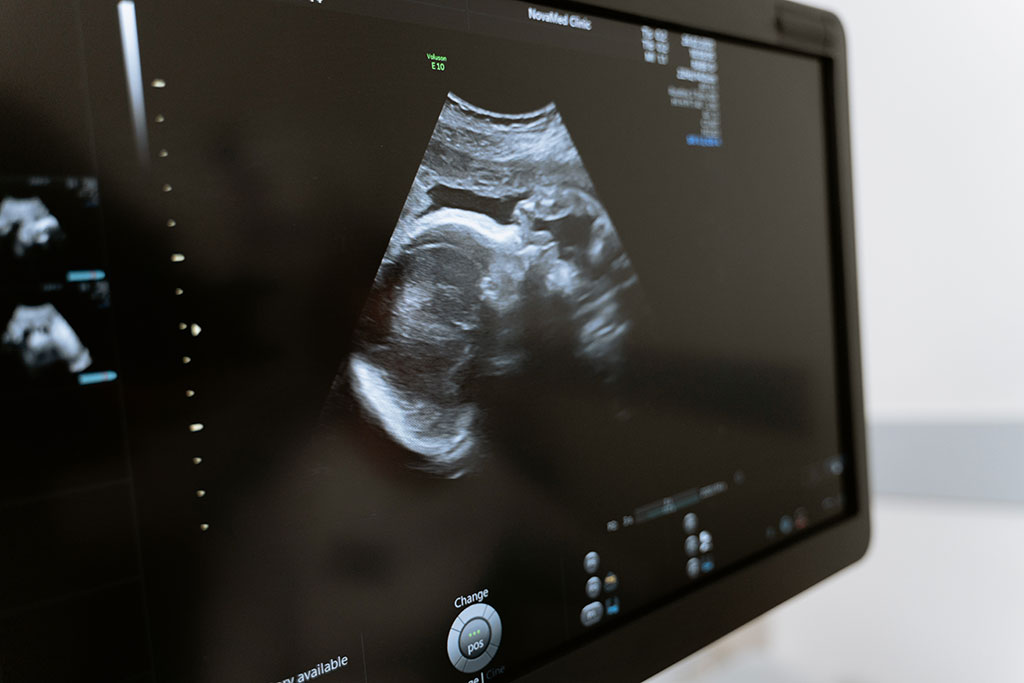

During the labor and delivery process, the uterus contracts to expel the fetus. Irregularities in these contractions can result in premature delivery or labor arrest, creating the need for a Cesarean (C-section) delivery. Both preterm birth and C-sections can increase the likelihood of injury or death for the parent and infant, potentially leading to long-term neurodevelopmental disability for the child. Identifying the specific type of uterine contractions that cause premature birth or labor arrest can aid researchers in developing methods to slow or prevent the onset of these contractions. However, current clinical techniques to measure uterine contractions, such as tocodynamometry and an intrauterine pressure catheter, are invasive and only provide limited information related to contraction duration and intensity.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine (St. Louis, MO, USA) have developed new imaging technology that can create 3D maps of uterine contractions in real-time, displaying both the magnitude and distribution of the contractions across the entire surface of the uterus during labor. Drawing from imaging methods frequently employed in examining the heart, this cutting-edge technology allows for noninvasive monitoring of uterine contractions with unprecedented detail, unlike currently available tools that only indicate the presence or absence of a contraction. The new imaging tool, called electromyometrial imaging (EMMI), provides real-time 3D images and maps of contractions during labor, generating new types of metrics and images that enable the quantification of contraction patterns. This groundbreaking non-invasive imaging technique lays the foundation for improved labor management, especially for preterm birth.

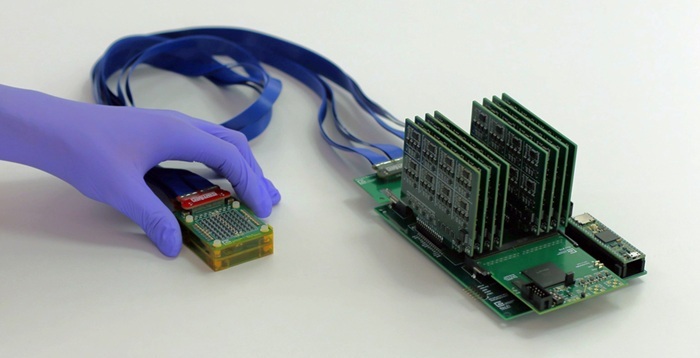

The EMMI technique integrates two types of noninvasive scans - a fast anatomical MRI used to capture a high-quality image of the uterus during the early term pregnancy stage (37 weeks gestation), and a multi-channel surface scanning electromyogram that utilizes sensors positioned along the abdominal region to monitor contractions during delivery. These data are then combined and processed into comprehensive three-dimensional uterine maps, which utilize warm colors to denote areas of the uterus that are activated earlier in a contraction, cool colors to display areas that are activated later, and gray areas to indicate inactive or non-contracting regions. Over time, a sequence of maps is created, producing a visual time lapse that shows where contractions originate, how they expand and/or synchronize, and any patterns that arise in a typical pregnancy versus one that may be experiencing difficulties or abnormalities.

In the new study, the team tailored EMMI for human clinical use and tested it among a group of 10 women with healthy pregnancies. The study revealed that uterine contractions exhibit less predictability and consistency than heart contractions measured using similar technology. Subsequent labor contractions can differ in the initiating region and the direction of progression even with the same patient. Additionally, the team discovered that initiation sites or "pacemakers" of the uterine contractions do not occur in fixed anatomical regions, as in the heart. These findings serve to increase the value of the EMMI imaging technology, as it is capable of tracking changes through progressive contractions.

The study featured primiparous (first-time birth) patients as well as multiparous (previously given birth) patients. The researchers discovered that primiparous patients exhibited longer contractions with greater variability than multiparous patients who had more efficient and productive contractions. This could be attributed to a "memory effect" of the uterus which may recall its previous labor experiences. The next objective of the researchers is to measure normal uterine contractions to discern whether they are productive and leading toward childbirth. In resource-restricted areas, such a detailed imaging technology could improve childbirth safety. To enhance accessibility, the researchers aim to swap costly MRI scans (uncommon in many regions globally) with less expensive, portable ultrasound imaging. Additionally, the team is creating disposable electrodes and wireless transmitters to promote mass usage of the technology.

“There are all kinds of obstetrics and gynecological conditions that are associated with uterine contractions, but we don’t have very accurate ways of measuring them,” said senior author Yong Wang, Ph.D., an associate professor of obstetrics & gynecology, of electrical & systems engineering, of radiology, and of biomedical engineering. “With this new imaging technology, we are basically upgrading the standard way of measuring labor contractions - called tocodynamometry - from one-dimensional tracing to four-dimensional mapping. This kind of information could help improve care for patients with high-risk pregnancies and identify ways to prevent preterm birth, which occurs in about 10% of pregnancies globally.”

Related Links:

Washington University School of Medicine