New MRI Method Detects Alzheimer’s Earlier in People without Clinical Signs

Posted on 07 Mar 2024

The current approach to evaluating patients for Alzheimer’s disease involves combining medical history reviews, neurological exams, cognitive and functional assessments, and additional tests like brain imaging, spinal taps, and blood tests. However, there's a pressing need for more cost-effective and earlier detection methods to pave the way for new clinical trials and interventions. Now, new research has uncovered a connection between unusual blood levels of amyloid — a protein linked with Alzheimer’s — and subtle changes in brain microstructures observable on a specific type of MRI. These findings could offer a novel avenue for detecting Alzheimer’s earlier in asymptomatic individuals.

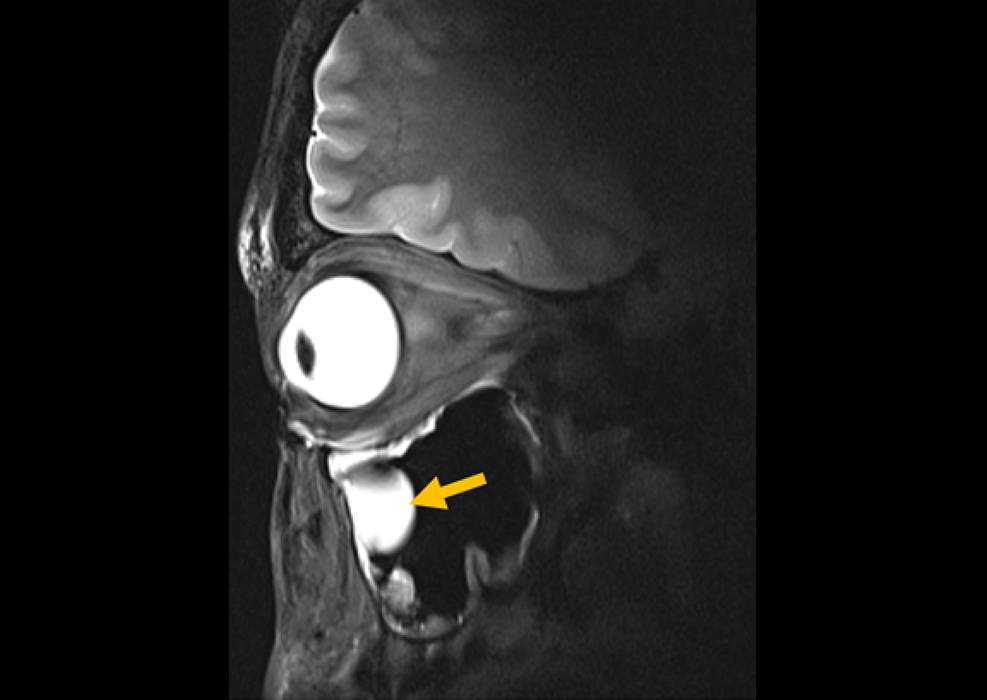

Researchers at University of Florida (Gainesville, FL, USA) conducted an analysis of 128 participants, both with and without dementia, who underwent positron emission tomography (PET) scans, a recognized tool for detecting amyloid plaques in the brain. The study revealed that even in cases where a PET scan failed to detect amyloid and the participant showed no dementia symptoms, there was still a link between abnormal blood amyloid levels and brain structural changes detected through an advanced imaging method known as diffusion MRI or "free-water" imaging. This research builds upon the team's previous work establishing free-water imaging as a reliable, noninvasive biomarker for Parkinson’s disease.

In this particular study, participants with amyloid-positive blood tests but amyloid-negative PET scans displayed brain alterations in diffusion MRI. These included reduced cortical volume and thickness, increased free-water across 24 brain regions, and diminished tissue microstructure in 66 areas. These findings suggest that free-water imaging is sensitive to early brain tissue and microstructural degeneration, even when PET scans show no signs of amyloid. The next phase of research aims to track these participants over time to observe if those with positive amyloid blood tests later develop positive amyloid PET scans. The focus will also be on understanding how free-water and blood amyloid levels change over time and correlate with symptoms, cognitive tests, and the eventual clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

“Previously people would say one of the earliest events you would see is amyloid positivity in the brain on a PET scan,” said senior author David Vaillancourt, Ph.D., a professor and chair of the UF College of Health & Human Performance’s department of applied physiology and kinesiology. “Our findings suggest there seem to be events occurring both in the blood and in the brain before you detect amyloid positivity in the brain.”

Related Links:

University of Florida