Low-Resolution Ultrasound Used to Measure Muscle Health

By MedImaging International staff writers

Posted on 18 Nov 2014

People suffering from muscular dystrophy could one day assess the effectiveness of their medication with the help of a smartphone-linked device. The new study used a new way to process ultrasound imaging data that could lead to hand-held devices to provide fast, effective medical information. Posted on 18 Nov 2014

In the study presented October 30, 2014, at the Acoustical Society of America’s (ASA) annual meeting, held in Indianapolis (IN, USA), researchers determined how well muscles damaged by muscular dystrophy responded to a drug in mice with an animal form of the disease. They did so by processing ultrasound data in a fashion suitable for small, low-power, and comparatively inexpensive instruments called point-of-care (POC) devices.

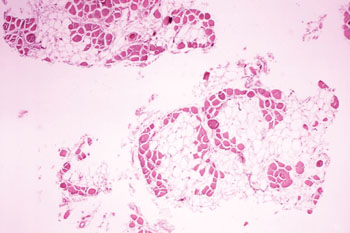

Image: In DMD muscles, light-colored fat cells invade the deep-colored cells of healthy muscle, creating a different ultrasound signature that can be converted into easy-to-understand values or signals to be displayed by a device to be used for monitoring muscle health (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

Physicist Michael S. Hughes of the US Department of Energy’s (DOE) Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (Richland, WA, USA) performed the work with colleagues Drs. John E. McCarthy, Jon N. Marsh, and Samuel A. Wickline, while at Washington University in St. Louis (MO, USA). Although a small study involving animals, it builds on research in individuals that reveals noninvasive ultrasound can track muscle health. Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) affects one out of 3,500 male births. Steroids can help slow muscle degeneration, but too much medication causes other issues such as weight gain and high blood pressure. “The result implies you can monitor drug therapy with cheap point-of-care devices,” said Dr. Hughes. “We’d like to be able to use low-power handheld instruments, such as a microphone-sized ultrasound that can fit on a smartphone.”

Healthcare workers and patients want fast, easy-to-use medical instruments and diagnostic tests that they can bring to a patient’s bedside, home or to the field. Some treatments for disease require constant monitoring, such as blood glucose in people with diabetes or blood pressure for those with heart disease.

In DMD, muscles cannot repair themselves sufficiently, causing the muscles to degenerate over a several decades. Young boys and men with the disease—whom DMD hits the most—typically take steroids to prolong muscle health. Steroids have serious side effects, so patients should only take as much as they need, but it is difficult to monitor effectiveness. Healthy muscle contains neatly ordered cells, but DMD muscles become fibrous and full of fat that infiltrates tissue. Because healthy and diseased muscles appear different in ultrasound images, researchers have been exploring how to use ultrasound to monitor progression of the disease and the muscle's response to drugs.

Previously, researchers have studied mice with genetic mutations that emulate muscular dystrophy. Treating mutant mice with steroids, they discovered they could process ultrasound information in such a way that they could measure the difference between healthy, damaged, and treated muscles—a technique that could put out a number on a screen.

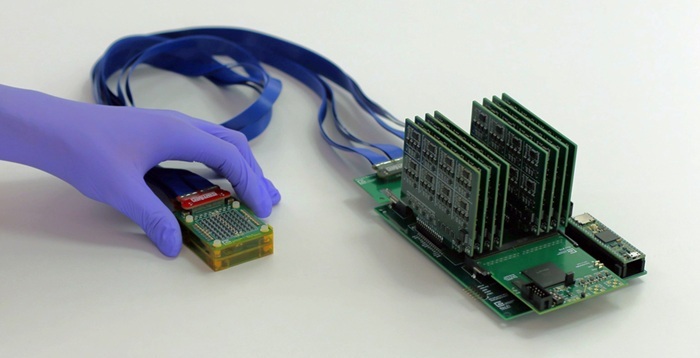

However, earlier research required more data than small, hand-held ultrasound devices, hooked into a smartphone with a universal serial bus (USB) cable, would be able to collect. Drs. Hughes and McCarthy wanted to see if they could also differentiate between healthy, diseased, and treated muscles if they collected less than 10% of the original data. They returned to the ultrasound data they had gathered on five healthy mice, four afflicted with mouse muscular dystrophy left untreated, and four afflicted but treated with steroids for two weeks.

To use less data, they needed to increase the pertinent information in the ultrasound data and suppress the irrelevant background noise. To do so, they used a mathematical trick called a spline, which streamlines the data into average values. With a spline added to their processing program, they re-analyzed either one-eighth or one-sixteenth of the data. The investigators discovered that even with only one-sixteenth of the data, they were able to measure the difference between the treated muscles and the untreated muscles. Because humans have much larger muscles than mice do, the researchers would have to adjust the amount of ultrasound data to account for that, but the researchers previously showed that is possible in different research.

“If we can optimize the processing, we can increase the sensitivity and provide real-time performance,” said Dr. Hughes. “People with muscular dystrophy have to take the least amount of steroid that will give them the maximum therapeutic effect. This would let them do that.”

Related Links:

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Washington University in St. Louis