Noninvasive Technique Monitors Fetal Heartbeat

By MedImaging International staff writers

Posted on 24 Jun 2009

Small fluctuations in a fetus's heartbeat can indicate distress, but currently there is no way to detect such slight variations except during labor, when it could be too late to prevent serious or even fatal complications. Now, a new technology could allow much earlier monitoring of the fetal heartbeat. Posted on 24 Jun 2009

Among other advantages, the system developed by a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT; Cambridge, MA, USA) scientist and colleagues, is expected to be less expensive and easier to use than current technologies. It could also slash the rate of Cesarean deliveries by helping clinicians rule out potential problems that might otherwise prompt the procedure. Lastly, the device used today to monitor subtle changes in the fetal heartbeat during labor must be attached to the fetus itself, but the new product would be noninvasive.

"Our objective is to make a monitoring system that's simultaneously cheaper and more effective” than what is currently available, stated Gari Clifford, Ph.D., a lead research scientist at the Harvard- (Cambridge, MA, USA)-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology. Dr. Clifford expects that the system could be commercially available in two to three years pending U.S. food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

While only a minority of pregnancies suffer from fluctuations in the fetal heartbeat, the issue is nonetheless critical because those that do can result in bad outcomes. These problems include certain infections and a loss of oxygen to the baby if strangled by the baby's own umbilical cord.

Clinicians currently have two ways to detect the fetal heartbeat. Ultrasound can detect the heartbeat quite early in a pregnancy. However, it is not sensitive enough to capture variations in the rhythm that could indicate problems. Electrocardiography (ECG), which records the electrical activity of the heart, can capture subtle changes in the fetal heartbeat. The problem until now has been that there is no way to effectively use the technique to that end except by attaching an electrode to the baby's scalp during labor.

Physicians can monitor the fetal ECG signal noninvasively through electrodes on the mother's abdomen, but it is weak compared to the maternal heartbeat and surrounding noise. Furthermore, it has not been possible to separate the three signals without distorting characteristics of the fetal heartbeat key to identifying potential clinical problems. "The dominant signal turns out to be the mother's heartbeat, so teasing out a tiny fetal signal in the background noise without altering the clinical meaning of the fetal signal is a problem that has proved virtually insoluble,” said Dr. Clifford.

The new technology separates the maternal ECG signal from the fetus' and background due to a complex algorithm derived from the fields of signal processing and source separation. Together, these fields work to break any signal into its source components.

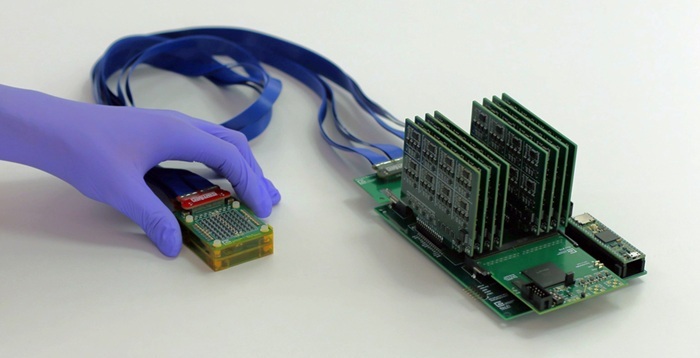

To use the system, which the team believes could be deployed during the second trimester of pregnancy (approximately 20 weeks) and perhaps earlier, a woman would wear a wide belt around her abdomen fitted with several ECG electrodes. (The prototype has 32, but that number will be lower in the final device.) The data collected from those electrodes are then fed to a monitor and analyzed with the new algorithm, which in turn separates the different signals.

Dr. Clifford noted that "one of the nice things about monitoring the fetal ECG through the mother's abdomen is you're getting a multidimensional view of the fetal heart” because its electrical activity is recorded from many different angles. The single probe now used to monitor the heartbeat during labor gives data from only one direction. "So with our system it's like going from a one-dimensional slice of an image to a hologram,” Dr. Clifford said. That better view could help catch problems that might have gone unnoticed before. "If you're looking in just one direction and an abnormality is occurring perpendicular to that direction, you won't see it,” Dr. Clifford said.

The large amounts of three-dimensional (3D) data captured with the new system could also open up a new field of research: fetal electrocardiography. "The world of fetal ECG analysis is almost completely unexplored,” Dr. Clifford said, because the current monitoring system can only be used during labor and "essentially gives only a monocular view.”

Dr. Clifford's major collaborator on the clinical work is Dr. Adam Wolfberg, an obstetrician and a fellow in maternal fetal medicine at Tufts Medical Center (Boston, MA, USA). To validate the algorithm and build the system, he turned to E-Trolz (North Andover, MA, USA).

Recently, several patent applications on the work were licensed by MindChild Medical, Inc. (Boston, MA, USA). The original development of the device was funded by the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology (CIMIT).

Related Links:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

E-Trolz