Residual Gadolinium May Persist in Brain for Years

By MedImaging International staff writers

Posted on 29 Dec 2016

New studies reveal that gadolinium based contrast agents (GBCA) used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exams may remain in the brain for years, but the long-term effects are unknown.Posted on 29 Dec 2016

A series of three recent studies raise new questions about residual gadolinium concentrations in the brains of patients with no history of kidney disease. The first, conducted at Teikyo University (Tokyo, Japan), examined brain tissues from five autopsied patients who had undergone multiple GBCA MRI exams and five patients with no gadolinium history. The study, published in the November 2016 issue of the Japanese Journal of Radiology, found that even in patients without severe renal dysfunction, gadolinium accumulated in the brain.

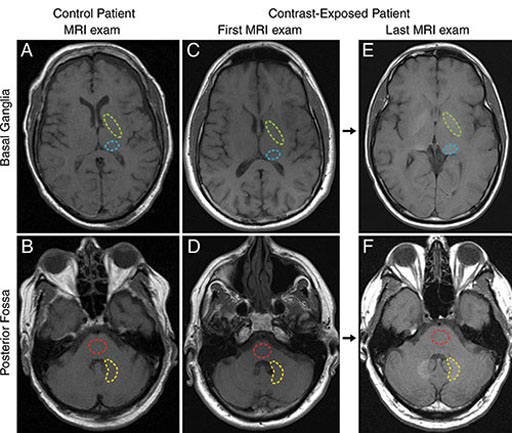

Image: Evidence of residual gadolinium in the brain (Photo courtesy of Emanuel Kanal/UPMC).

The findings of the Japanese study lend support to the results of a study at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA), published in the March 2016 issue of Radiology, which showed residual gadolinium deposits present in the postmortem brains of 13 patients who had undergone at least four GBCA contrast MRI exams. Neither the Teikyo University nor the Mayo clinic study was able to identify whether the residual gadolinium was in free or chelated form.

A third study, by the University of Heidelberg (Germany), published in the June 2015 issue of Radiology, retrospectively looked at two groups of 50 patients who had undergone at least six MRI exams, suggests that the molecular structure of the gadolinium contrast agent may play a role in retention. There are two structurally distinct categories of GBCA: linear and macrocyclic. In the macrocyclic structure, the gadolinium is bound more tightly to the chelating agent and, therefore, less likely to release free gadolinium into the body.

“We now have clear evidence that the administration of various gadolinium-based contrast agents results in notably varied levels of accumulation of residual gadolinium in the brain. What we still don’t know is the clinical significance, if any, of this observation,” commented professor of radiology and neuroradiology Emanuel Kanal, MD, director of magnetic resonance services at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC, PA, USA). “We cannot unnecessarily deprive our patients of crucial, even life-saving medical data from gadolinium contrast-enhanced MRI. Nor can we ignore these new findings and continue prescribing them as we have until now, without change.”

Gadolinium--a rare earth heavy metal--is used for enhancement during MRI. Neurotoxic effects have been seen in animals and when a GBCA is given intrathecally in humans. On its own, gadolinium can be toxic; therefore, when used in contrast agents, gadolinium is bonded with a molecule called a chelating agent, which controls the distribution of gadolinium within the body. In July 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stated that it was unknown whether gadolinium deposits in the brain were harmful.

Related Links:

Teikyo University

Mayo Clinic

University of Heidelberg

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center