In Veterans with PTSD, PET/CT Imaging Reveals Pituitary Abnormalities

By MedImaging International staff writers

Posted on 16 Dec 2014

Hybrid imaging with positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET/CT) in the pituitary region of the brain has been shown to be a potential new approach for distinguishing military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from those with mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI).Posted on 16 Dec 2014

The study’s findings were presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), held November 30 to December 5, 2014, in Chicago (IL, USA). Moreover, these findings build support to the hypothesis that many veterans diagnosed with PTSD may actually have hormonal irregularities caused by pituitary gland damage from blast injury.

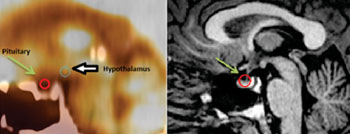

Image: PET/CT on the left and an MRI on the right demonstrating the relative locations of both the hypothalamus and the pituitary (Photo courtesy of RSNA).

MTBI involves injury to the brain from an external force, while PTSD is typically defined as a mental health disorder that can develop after someone has experienced a traumatic event. Research has shown that up to 44% of returning veterans with MTBI and loss of consciousness also meet the criteria for PTSD. Differentiating PTSD from MTBI can be problematic for clinicians because of symptom overlap, and in many instances, normal structural neuroimaging results.

Researchers recently used PET/CT to study the hypothalamus and pituitary glands of veterans who had suffered blast-related MTBI. The pituitary gland is a pea-sized structure that sits in the bony enclosure located at the base of the skull and is connected to a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. Together with the adrenal glands above each kidney, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland form the HPA axis, an important regulator of many body processes, including mood, stress response, and energy expenditure.

“The HPA axis is a complex system with a feedback loop, so that damage to any one of the three areas will affect the others,” said study lead author Thomas M. Malone, BA, from the department of neurosurgery at Saint Louis University School of Medicine (Saint Louis, MO, USA). “It’s suspected of playing an important role in PTSD, but there is limited neuroimaging research in the veteran population.”

The investigators centered on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT, which provides a picture of metabolism by measuring uptake of the radiopharmaceutical FDG. A review of 159 brain 18F-FDG PET/CT scan records revealed that FDG uptake in the hypothalamus was significantly lower in the MTBI-only group compared with normal controls. FDG uptake in the pituitary gland was substantially raised in the MTBI and PTSD group compared with the MTBI-only group.

The finding of higher FDG uptake in the pituitary glands of PTSD sufferers supports the theory that many veterans diagnosed with PTSD may actually have hypopituitarism, a condition in which the pituitary gland does not produce normal amounts of one or more of its hormones. “This raises the possibility that some PTSD cases are actually hypopituitarism masking itself as PTSD,” Dr. Malone said. “If that’s the case, then we might be able to help those patients by screening for hormone irregularities and treating those irregularities on an individual basis.”

Dr. Malone reported that the increased FDG uptake in the pituitary glands of veterans with MTBI and PTSD may be due to the gland working harder to produce hormones. “It’s analogous to having your car stuck in the snow and you keep flooring the gas pedal but you don't go anywhere,” he said.

The findings suggest that PET/CT may provide an effective way to diagnose and differentiate PTSD from MTBI and offer more clues into the biologic manifestations of the disorder. “This study sheds light on the complex issue of PTSD, which also has symptom overlap with depression and anxiety,” Dr. Malone concluded. “Currently, treatment for PTSD is typically limited to psychological therapy, antidepressants and anxiety medications. Our findings reinforce the theory that there is something physically and biologically different in veterans who have MTBI and PTSD compared to those who just have MTBI.”

Related Links:

Saint Louis University School of Medicine