New Imaging Technique Provides Clues Toward Spinal Cord Regeneration

By MedImaging International staff writers

Posted on 01 Jul 2009

Using a novel imaging approach, researchers have discovered that the axons also regrow in the direction of the spinal cord within a short lapse of time after the injury. Moreover, this regrowth is encouraged by posttraumatic angiogenesis (by the process of formation of new blood vessels in the damaged tissue).Posted on 01 Jul 2009

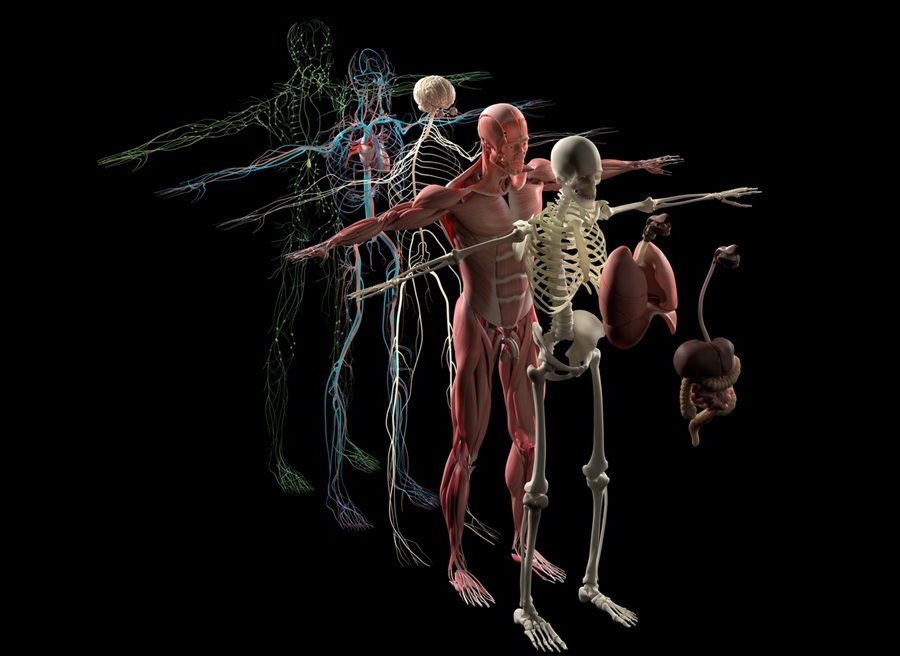

The axon is a part of the neuron through which nerve impulses are transmitted, and at the end of which is located the synapse, which connects it to another neuron. In the event of a lesion, the axon is the component that must be regenerated in order to restore the connections between the different neurons and re-form the nerve.

The regeneration capacity of axons within the central nervous system, of which the spinal cord is part, has until now been much debated. Axons can regenerate toward the muscles, whereas in the opposite direction inhibiting factors prevent regrowth toward the nerve centers. This new research was conducted by Dr. Geneviève Rougon's team from the Institut de Biologie du Dévelopement de Marseille Luminy (IBDML; France).

After injury to a mouse's spinal cord, extensive and extremely active angiogenesis is observed, peaking in intensity one week after the lesion. At the same time, regrowth of the axons takes place preferentially and more rapidly near the blood vessels. These observations suggest that stimulating and prolonging angiogenesis could open up new prospects for treatment and encourage functional recovery after, for instance, lesion of the spinal cord.

This spatiotemporal interaction was described by the combination two new techniques in imaging: the use of mice whose cell populations can be observed due to their fluorescent properties, and two-photon microscopy. This new imaging protocol makes it possible to display in situ and in three dimensions (3D), the cell phenomena that come into play under traumatic or pathologic conditions, and to characterize their dynamics by means of repeated observations of the same mouse. In this way, cell interactions can be described dynamically, over space and time, in a live animal, something that is impossible to do with conventional histologic techniques, which require the sacrifice of several animals at each relevant stage. This noninvasive technique drastically reduces the number of mice used, and since the experiment can be reproduced using the same animal, considerably improves the result.

In addition to its importance for essential research, such a combination opens up new prospects for preclinical research, according to the investigators. In the field of pharmacology, for instance, this kind of dynamic imaging could make it possible to precisely define application protocols for medicines, and better control their effects and adjust dosage.

Related Links:

Institut de Biologie du Dévelopement de Marseille Luminy