Night Vision Technology Used to Learn More about Lymphatic System

By MedImaging International staff writers

Posted on 26 May 2009

U.S. scientists are using near-infrared night vision technology to provide insights into the lymphatic system. Posted on 26 May 2009

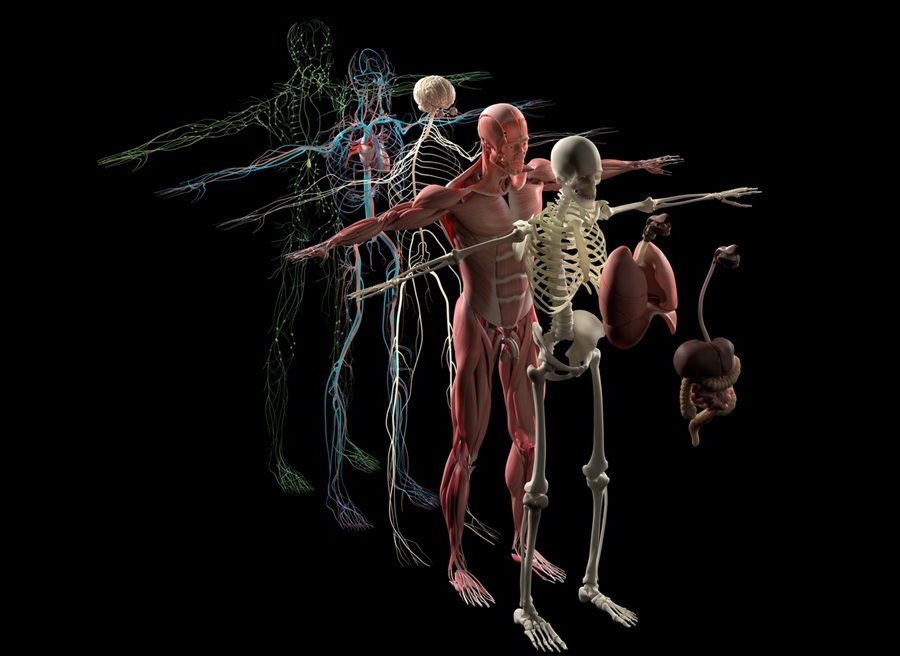

While much is known about the blood system, Eva Sevick, Ph.D., a professor of molecular medicine and leader of the 20-person research team in the University of Texas' Brown Foundation Institute of Molecular Medicine for the Prevention of Human Diseases (IMM; Houston, USA), reported that until recently comparatively little was known about the lymphatic system, which is a network of vessels that act as the body's sewer system, gathering excess debris and fluid from tissues.

Unlike blood, lymphatic fluid is clear, which makes it hard to see. Moreover, lymphatic vessels are so small that it is difficult to inject the amount of contrast agents needed for conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or X-rays. While lymphatic fluid can be seen with nuclear techniques, actual fluid movement is difficult to observe because it typically takes several minutes to acquire an image.

Dr. Sevick's solution to these medical imaging issues was to inject micro-amounts of fluorescent dye below the skin where the lymphatic system would sweep it up. Then with the aid of a small laser and a night vision camera designed to pick up small amounts of light, Dr. Sevick's team was able to observe the dye move through the lymph system below the surface of the skin. This was possible because the night vision camera can acquire images in less than one second.

"No one had ever watched this before,” said Caroline Fife, M.D., clinical associate professor of medicine at The University of Texas Medical School at Houston. "This was like Christopher Columbus discovering America. Until now, we've never had a good way to study the lymph system. It felt like being a doctor before antibiotics.”

When the lymphatic system is functioning correctly, it picks up fluids that leak from blood vessels into the spaces between cells. As this fluid passes between cells it gathers cell waste and debris. The fluid is subsequently taken up by tiny lymphatic capillaries and propelled through lymphatic ducts and nodes until it is returned to the blood.

The lymphatic system also contains immune cells named lymphocytes, which guard the body against invading viruses and bacteria. The lymphatic system is of specific interest to cancer specialists because malignant cells will often end up in lymphatic filters. "Lymph nodes filter out bacteria and tumor cells,” stated Dr. Fife, noting that the lymphatic system processes 6 l of fluid every day.

Similar to plumbing when it backs up, lymphatic drainage problems can cause fluid retention or swelling, which results in a condition called lymphedema. While there is no cure, lymphedema symptoms can sometimes be treated with massage and compression bandaging. "The Center for Molecular Imaging is poised to develop and translate molecular imaging agents, instruments, and computer algorithms for improving patient care in a variety of diseases,” Dr. Sevick said. "With our optical technologies, we could image disease before the onset of symptoms. We also investigate the impact of breast cancer therapy on lymphatic function in order to evaluate how long-term treatments impact quality of life for cancer survivors.”

Dr. Sevick is working to convert her bench discoveries into patient care. With the approval of the U. S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA), the researchers in her lab have begun patient trials using this medical imaging technique, which could aid in the diagnosis and treatment of many diseases including those of the lymphatic system.

In one trial, Dr. Sevick's team is recruiting 18 individuals for a clinical study to determine the effect of an automated massage device on lymphatic flow in individuals with lymphedema of either one arm or one leg. In a second study, her research team is studying the effect of genetic makeup in persons with hereditary lymphedema and acquired lymphedema.

Related Links:

Brown Foundation Institute of Molecular Medicine for the Prevention of Human Diseases